Resources - The BBC Prison Study

Overview

Introduction

In these pages we provide resources for readers who want to go further and find out more – both about the BBC Prison Study itself and about the issues it raises.

First, we explore ideas related to the design of the study and its findings.

Second, we provide details of the various scientific publications that have come out of the study (many of which are available to be downloaded here).

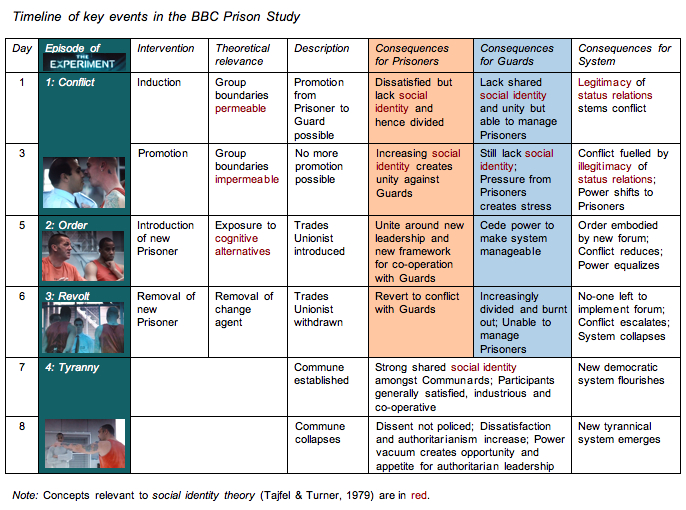

Third, we provide a table which summarizes the timeline of the study.

Fourth, we provide details of the quantitative data that we collected during the study. These serve to validate our qualitative narrative and also underline the point that our claims about the study are backed up by solid scientific evidence.

Fifth, we explain how to obtain further materials relating to the study (DVDs, transcripts and manuals).

Sixth, we provide a list links to other relevant websites.

Seventh, we provide a glossary of the various psychological terms used in this website.

These resources are intended to be of particular use for teachers and students. If you have any suggestions for additional material that we could provide and that would be helpful to you or others, please let us know.

Ideas in depth

Individuals and groups

The relationship between the individual and the group is one of the core issues of social psychology.

Is group behaviour simply the sum of the characteristics of individual group members? Put a load of aggressive people together and you will have an aggressive group. Raise a generation of authoritarians and you will have an authoritarian society.

Or are individuals transformed in the group so that, say, where two groups are in competition, all members become conflictual and hostile? Or, if the role of the group is to be oppressive, will individual members inevitably become oppressive?

Historically, there has been something of a shift from the first position (individualism) to the second (situationism). The Stanford Prison Experiment is possibly the most powerful expression of the view that situations overwhelm individuals.

The position we advocate (dynamic interactionism) argues for the contribution of both group situation and individual. First, individuals are drawn to groups whose ideologies match their own. Second, individuals are transformed by being members of groups. But, third, individuals can transform groups when they are seen to exemplify group norms and values.

More generally, groups do not turn people into robots or zombies. Rather, they provide a framework for people to make sense of their world and to be effective within it.

Further reading

- Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2007). Beyond the banality of evil: Three dynamics of an interactionist social psychology of tyranny. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 615-622.

- Postmes, T. & Jetten, J. (Eds.) (2006). Individuality and the group: Advances in social identity. London: Sage.

- Reynolds, K. J., Turner, J. C., Branscombe, N. R., Mavor, K. I., Bizumic, B., & Subasic, E. (in press). Interactionism in personality and social psychology: An integrated approach to understanding the mind and behaviour. European Journal of Personality.

Ideas in depth

Social identity theory

Social identity theory proposes that, when acting in groups, we define ourselves in terms of our group membership and seek to have our group valued positively relative to other groups. So if we define ourselves in terms of our nationality (e.g., as American, Australian or British), we want our country to look good compared to other countries.

However, in our unequal world, many people find themselves in groups that are devalued compared to others – for instance, black people in a racist world. What do they do then?

Social identity theory argues that this depends upon two factors. The first is permeability. If we believe that we can still progress in society despite our group membership (i.e., group boundaries are permeable) we will try to distance ourselves from the group and be seen as an individual. If there is no chance of advancement (because group boundaries are impermeable), we will begin to identify with the group and act collectively with fellow group members to improve our situation.

What we do as group members depends upon the second factor: security. If we believe that the present situation is either legitimate or inevitable, we will adapt to it. We may seek to improve the valuation of our own group (e.g., by stressing new positive characteristics) but we won’t question the system itself. However, if we see the situation as illegitimate and we can envisage other ways of organizing society (cognitive alternatives) then we will act collectively to challenge the status quo and bring about social change.

Further reading

- Ellemers, N., Spears, R. & Doosje, B. (1999). Social identity: Context, content and commitment. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Ideas in depth

Leadership

The traditional view of leadership is that particular people have inherent qualities which set them apart from others and make them natural leaders. However, there is no evidence of such qualities. Indeed, the qualities which make for successful leadership vary from situation to situation. This has led to ‘contingency’ models that try to specify what qualities lead to success in different situations. Such models have not proved much more successful.

This is because traditional approaches forget that all leaders are leaders of some group: a nation, of a political party, of a church or whatever. And what binds followers to a leader is the fact that both are bound together within the group. That is, we see someone as a leader to the extent that they represent the group that we identify with.

There are three important implications of this position:

First, leadership is only possible where a set of people share a common group identity. If there is no ‘we’ and no shared norms and values that ‘we’ believe in, then there is nothing for a would-be leader to represent.

Second, the most effective leader will be the person who is most typical of the group (the person whose prototypicality is highest) and hence able to best represent the shared group identity.

Third, leaders will actively shape the group identity in order to make themselves and their plans seem representative. That is, successful leaders need to be skilled ‘entrepreneurs of identity’.

These are ideas that we explore in greater depth in our recent book The New Psychology of Leadership. As well as discussing leadership in the BBC Prison Study, this presents a wealth of other data from experimental, historical and field settings, and integrates this within the framework of a new analysis of leadership informed by social identity theorizing.

Further reading

- Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D. & Platow, M. J. (2011). The new psychology of leadership: Identity, influence and power. New York: Psychology Press.

- van Knippenberg, D., & Hogg, M. A. (Eds.) (2003). Leadership and power: Identity processes in groups and organizations. London: Sage.

Ideas in depth

Stress and burnout

In the workplace and in organizational psychology it is common for people to think that only particular individuals are likely fall victim to the pressures of stress and to experience burnout – those who are insufficiently resilient or hardy.

In contrast, our study makes it clear that whether people are exposed to stressors and what strategies they use to deal with them both depend very much on features of social context that impact upon their group and their sense of social identity.

In particular, we can see that these factors determine the different coping strategies that people resort to in order to deal with stress.

Avoidance – attempting to escape from the stressor – is a strategy that people are likely to prefer when they are isolated and lack support from other group members.

Denial – attempting to redefine the stressor – is a strategy that people prefer when opportunities for escape are limited, but when the stressor cannot be directly challenged.

Resistance – attempting to confront and remove a stressor – is a strategy that people are more likely to adopt when they have support from fellow group members and are aware of cognitive alternatives that suggest the possibility of social change.

Further reading

- Maslach, C. & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Schmitt, M. T., & Branscombe, N. R. (2002). The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged social groups. European Review of Social Psychology, 12, 167-199.

Ideas in depth

Tyranny and evil

Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) gave rise to a simple and powerful explanation of why people do evil things. Put them in a group and they will automatically take on their roles. In the SPE, it is claimed, guard aggression “was emitted simply as a ‘natural’ consequence of being in the uniform of a ‘guard’ and asserting the power inherent in that role”.

The logic of this position is that because people can’t help themselves, they have limited responsibility for their actions. Indeed, Zimbardo has followed through on this logic and acted as an expert in defence of one of the American guards found guilty of abusing inmates at Abu Ghraib prison. The guards, he asserts, "were essentially clueless as to what was appropriate and what was not acceptable when preparing detainees for detention".

An alternative perspective is to argue that people do have choices in groups. They have choice over joining. They have choice over what they do as members. Those who give orders to abuse others clearly bear much of the responsibility, but that doesn’t absolve those who follow the orders.

In fact, both historical and psychological evidence suggests that people who commit atrocities know what they are doing and believe in what they are doing. They identify with the cause, they see their ‘victims’ as threats to the cause, and they see their actions as a ‘noble’ defence of the cause. The problem here is not that group psychology makes people thoughtless. It is that some group ideology can make people zealots.

Further reading

- Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. New York: Penguin.

- Cesarani, D. (2004). Eichmann: His life and crimes. London: Heinemann.

- Zimbardo, P. (2007). The Lucifer Effect: How good people turn evil. London: Random House.

Publications

Information

Findings from the BBC Prison Study have been published in a series of articles in leading peer-reviewed scientific journals as well as in books edited by leading academics.

These articles address the range of issues explored in the study, including tyranny and social issues, leadership and organizational issues and stress and clinical issues.

Several articles also provide overviews of the study and a number of researchers have provided commentary on the study and the issues it raises.

These publications are available either by clicking on the download links here, or by contacting the researchers.

Publications

Overviews of the study

Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2012). Contesting the “nature” of conformity: What Milgram and Zimbardo's studies really show. PLoS Biology, 10 (11): e1001426.

doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001426

- Abstract: Understanding of the psychology of tyranny is dominated by classic studies from the 1960s and 1970s: Milgram's research on obedience to authority and Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment. Supporting popular notions of the banality of evil, this research has been taken to show that people conform passively and unthinkingly to both the instructions and the roles that authorities provide, however malevolent these may be. Recently, though, this consensus has been challenged by empirical work informed by social identity theorizing. This suggests that individuals' willingness to follow authorities is conditional on identification with the authority in question and an associated belief that the authority is right.

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2012). When prisoners take over the prison: A social psychology of resistance. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16, 154-179.

.jpg)

- Abstract: There is a general tendency for social psychologists to focus on processes of oppression rather than resistance. This is exemplified and entrenched by the Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE). Consequently, researchers and commentators have come to see domination, tyranny, and abuse as natural or inevitable in the world at large. Challenging this view, research suggests that where members of low-status groups are bound together by a sense of shared social identity this can be the basis for effective leadership and organization that allows them to counteract stress, secure support, challenge authority, and promote social change in even the most extreme of situations. This view is supported by a review of experimental research — notably the SPE and the BBC Prison Study — and case studies of rebellion against carceral regimes in Northern Ireland, South Africa, and Nazi Germany. This evidence is used to develop a Social Identity Model of Resistance Dynamics.

Reicher, S. D. & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1–40.

![]()

- Abstract: This paper presents findings from the BBC Prison Study: an experimental case study that examined the consequences of randomly dividing men into groups of prisoners and guards within a specially constructed institution over a period of eight days. Unlike the prisoners, the guards failed to identify with their role. This made the guards reluctant to impose their authority and they were eventually overcome by the prisoners. Participants then established an egalitarian social system. When this proved unsustainable, moves to impose a tyrannical regime met with weakening resistance. Empirical and theoretical analysis addresses the conditions under which people identify with the groups to which they are assigned and the social, organizational and clinical consequences of either doing so or failing to do so. On the basis of these findings a newframework for understanding tyranny is outlined. This suggests that it is powerlessness and the failure of groups that makes tyranny psychologically acceptable.

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2005).

The psychology of tyranny. Scientific American Mind, 16 (3), 44–51.

![]()

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2004).

Visión crítica de la explicación de la tiranía basada en los roles: Pensando más allá del Experimento de la Prisión de Stanford. Revista de Psicología Sociale, 19, 115-122.

![]()

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2003).

Beyond Stanford: Questioning a role-based explanation of tyranny. Dialogue (Bulletin of the Society of Personality and Social Psychology), 18, 22-25.

![]()

Publications

On evil and society

Reicher, S. D, Haslam, S.A., & Rath, R. (2008).

Making a virtue of evil: A five-step social identity model of the development of collective hate. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1313-1344.

![]()

- Abstract: In the first part of this paper, we re-examine the historical and psychological case for 'the banality of evil'– the idea that people commit extreme acts of inhumanity, and more particularly genocides, in a state where they lack awareness or else control over what they are doing. Instead, we provide evidence that those who commit great wrongs knowingly choose to act as they do because they believe that what they are doing is right. In the second part of the paper, we then outline an integrative five-step social identity model that details the processes through which inhumane acts against other groups can come to be celebrated as right. The five steps are: (i) Identification, the construction of an ingroup; (ii) Exclusion, the definition of targets as external to the ingroup; (iii) Threat, the representation of these targets as endangering ingroup identity; (iv) Virtue, the championing of the ingroup as (uniquely) good; and (v) Celebration, embracing the eradication of the outgroup as necessary to the defence of virtue.

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2007).

Beyond the banality of evil: Three dynamics of an interactionist social psychology of tyranny. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 615-622.

![]()

- Abstract: Carnahan and McFarland (2007) critique the situationist account of the Stanford Prison Experiment by arguing that understanding extreme action requires consideration of individual characteristics and the interaction between person and situation. We develop this argument in two ways. First, we reappraise historical and psychological evidence that supports the broader ‘banality of evil’ thesis – the idea that ordinary people commit atrocities without awareness, care or choice. Counter to this thesis we show that perpetrators act thoughtfully, creatively, and with conviction. Second, drawing from this evidence and the BBC Prison Study (Reicher & Haslam, 2006a), we make the case for an interactionist approach to tyranny which explains how people are (a) initially drawn to extreme and oppressive groups, (b) transformed by membership in those groups, and (c) able to gain influence over others and hence normalize oppression. These dynamics can make evil appear banal, but are far from banal themselves.

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2007).

Questioning the banality of evil. The Psychologist, 21, 16-19.

![]()

- Abstract: There is a widespread consensus amongst psychologists that tyranny triumphs either because ordinary people blindly follow orders or else because they blindly conform to powerful roles. However, recent historical evidence challenges these views. In particular, studies of the Nazi regime reveal that its functionaries engaged actively and creatively with their tasks. Re-examination of classic social psychological studies points to the same dynamics at work. This article summarizes these developments and lays out the case for an updated social psychology of tyranny that explains both the influence of tyrannical leaders and the active contributions of their followers.

Reicher, S. D. & Haslam, S. A. (2006).

On the agency of individuals and groups: Lessons from the BBC Prison Study. In T. Postmes & J. Jetten (Eds.) Individuality and the group: Advances in social identity (pp.237-257). London: Sage.

![]()

Publications

On leadership and organization

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2007).

Identity entrepreneurship and the consequences of identity failure: The dynamics of leadership in the BBC Prison Study. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70, 125-147.

![]()

- Abstract: The BBC Prison Study was an experimental case study in which participants were randomly assigned to groups as prisoners or guards. This paper examines the impact of interventions designed to increaseprisoners’ sense of shared social identity on processes of leadership. It presents psychometric, behavioral and observational data which support the propositions that (a) social identity makes leadership possible, (b) effective leadership facilitates the development of social identity, and (c) the long-term success (and failure) of leadership depends of the viability of identity-related projects. The study also points to the role of identity failure in precipitating change in general and the emergence of authoritarian leadership in particular. Findings provide integrated support for claims that social identity and self-categorization processes are fundamental to the leadership process and associated experiences of collective efficacy.

Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2007).

Social identity and the dynamics of organizational life: Insights from the BBC Prison Study. In C. Bartel, S. Blader, & A. Wrzesniewski (Eds.) Identity and the modern organization (pp.135–166). New York: Erlbaum.

![]()

Reicher, S. D., Haslam, S. A. & Platow, M. J. (2007).

The new psychology of leadership. Scientific American Mind, 17 (3), 22-29.

![]()

Reicher, S. D., Haslam, S. A., & Hopkins, N. (2005).

Social identity and the dynamics of leadership: Leaders and followers as collaborative agents in the transformation of social reality. Leadership Quarterly, 16, 547–568.

![]()

- Abstract: Traditional models see leadership as a form of zero-sum game in which leader agency is achieved at the expense of follower agency and vice versa. Against this view, the present paper argues that leadership is a vehicle for social identity-based collective agency in which leaders and followers are partners. Drawing upon evidence from a range of historical sources and from the BBC Prison Study, the present paper explores the two sides of this partnership: the way in which a shared sense of identity makes leadership possible and the way in which leaders act as entrepreneurs of identity in order to make particular forms of identity and their own leadership viable. The analysis also focuses (a) on the way in which leaders’ identity projects are constrained by social reality and (b) on the manner in which effective leadership contributes to the transformation of this reality through the initiation of structure that mobilizes and redirects a group’s identity-based social power.

Publications

On stress and well-being

Reicher, S. D. & Haslam, S. A. (2006).

Tyranny revisited: Groups, psychological well-being and the health of societies. The Psychologist, 19, 46–50.

![]()

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2006).

Stressing the group: Social identity and the unfolding dynamics of stress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1037–1052.

![]()

- Abstract: Participants in the BBC Prison Study were randomly assigned to high-status (guard) and low-status (prisoner) groups. Structural interventions increased the prisoners’ sense of shared group identity and their willingness to challenge the power of the guards. Psychometric, physiological, behavioral, and observational data support the hypothesis that identity-based processes also affected participants’ experience of stress. As prisoners’ sense of shared identity increased they provided each other with more social support and effectively resisted the adverse effects of situational stressors. As guards’ sense of shared identity declined they provided each other with less support and succumbed to stressors. Findings support an integrated social identity model of stress (ISIS) that addresses intragroup and intergroup dynamics of the stress process.

Publications

Commentaries on the study

Turner, J. C. (2006).

Tyranny, freedom and social structure: Escaping our theoretical prisons. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 41–46.

![]()

- Abstract: Reicher and Haslam’s (2006) BBC prison study undermines the idea that people passively accept and enact social roles. In this commentary, I point out that this idea is an example of Moscovici’s (1976) conformity bias and a wider stability bias in social psychological theorizing. In many key areas, the science prefers analyses that explain how and why social structures, intergroup and power relations, personalities and beliefs maintain and reproduce themselves, and indeed cannot be changed, rather than how and why society constantly generates forces for social change from within itself. This bias distorts reality and produces ideas of limited theoretical or practical power. Human psychology does not make us prisoners of social structure. It makes us capable of collective action to change social structures and in turn re-fashion our identities, roles, personalities and beliefs. Society is not a psychological prison but a means of expanding human possibilities. A reorientation of theoretical emphasis is overdue.

Zimbardo, P. (2006).

On rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 47–53.

![]()

- Abstract: This commentary offers a critical evaluation of the scientific legitimacy of research generated by television programming interests. It challenges the validity of claims advanced by these researchers regarding the Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) and highlights the biases, fallacies and distortions in this study conducted for BBC-TV that attempted a partial replication of my earlier experiment.

Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2006).

Debating the psychology of tyranny: Fundamental issues of theory, perspective and science. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 55–63.

![]()

- Abstract: In this rejoinder we concentrate on responding to Zimbardo’s criticisms. These criticisms involve three broad strategies. The first is to turn broad discussion about the psychology of tyranny into narrow questions about the replication of prison conditions. The second is to confuse our scientific analysis with the television programmes of ‘The Experiment’. The third is to make unsupported and unwarranted attacks on our integrity. All three lines of attack are flawed and distract from the important theoretical challenge of understanding when people act to reproduce social inequalities and when they act to challenge them. This is the challenge that Turner identifies and engages with in his commentary.

Publications

On Milgram's 'obedience' research

Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2017).

50 Years of “Obedience to Authority”: From blind conformity to engaged followership. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 59–78.

doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113710

- Abstract: Despite being conducted half a century ago, Stanley Milgram's studies of obedience to authority remain the most well-known, most controversial, and most important in social psychology. Yet in recent years, increased scrutiny has served to question the integrity of Milgram's research reports, the validity of his explanation of the phenomena he reported, and the broader relevance of his research to processes of collective harm-doing. We review these debates and argue that the main problem with received understandings of Milgram's work arises from seeing it as an exploration of obedience. Instead, we argue that it is better understood as providing insight into processes of engaged followership, in which people are prepared to harm others because they identify with their leaders' cause and believe their actions to be virtuous. We review evidence that supports this analysis and shows that it explains the behavior not only of Milgram's participants but also of his research assistants and of the textbook writers and teachers who continue to reproduce misleading accounts of his work..

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., & Birney, M. E. (2016).

Questioning authority: New perspectives on Milgram's 'obedience' research and its implications for intergroup relations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 6–9.

doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.007

- Abstract: Traditionally, Milgram's ‘obedience’ studies have been used to propose that ‘ordinary people’ are capable of inflicting great harm on outgroup members because they are predisposed to follow orders. According to this account, people focus so much on being good followers that they become unaware of the consequences of their actions. Atrocity is thus seen to derive from inattention. However recent work in psychology, together with historical reassessments of Nazi perpetrators, questions this analysis. In particular, forensic re-examination of Milgram's own findings, allied to new psychological and historical research, supports an ‘engaged follower’ analysis in which the behaviour of perpetrators is understood to derive from identification with, and commitment to, an ingroup cause that is believed to be noble and worthwhile.

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., & Millard, K. (2015).

Shock treatment: Using Immersive Digital Realism to restage and re-examine Milgram’s ‘Obedience to Authority’ research. PLoS ONE, 10(3): e109015.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109015

- Abstract: Attempts to revisit Milgram’s ‘Obedience to Authority’ (OtA) paradigm present serious ethical challenges. In recent years new paradigms have been developed to circumvent these challenges but none involve using Milgram’s own procedures and asking naïve participants to deliver the maximum level of shock. This was achieved in the present research by using Immersive Digital Realism (IDR) to revisit the OtA paradigm. IDR is a dramatic method that involves a director collaborating with professional actors to develop characters, the strategic withholding of contextual information, and immersion in a real-world environment. 14 actors took part in an IDR study in which they were assigned to conditions that restaged Milgrams’s New Baseline (‘Coronary’) condition and four other variants. Post-experimental interviews also assessed participants’ identification with Experimenter and Learner. Participants’ behaviour closely resembled that observed in Milgram’s original research. In particular, this was evidenced by (a) all being willing to administer shocks greater than 150 volts, (b) near-universal refusal to continue after being told by the Experimenter that “you have no other choice, you must continue” (Milgram’s fourth prod and the one most resembling an order), and (c) a strong correlation between the maximum level of shock that participants administered and the mean maximum shock delivered in the corresponding variant in Milgram’s own research. Consistent with an engaged follower account, relative identification with the Experimenter (vs. the Learner) was also a good predictor of the maximum shock that participants administered.

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., Millard, K., & McDonald, R. (2014).

“Happy to have been of service”: The Yale archive as a window into the engaged followership of participants in Milgram’s ‘obedience’ experiments. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54, 55-83.

doi:10.1111/bjso.12074

- Abstract: This study examines the reactions of participants in Milgram's ‘Obedience to Authority’ studies to reorient both theoretical and ethical debate. Previous discussion of these reactions has focused on whether or not participants were distressed. We provide evidence that the most salient feature of participants’ responses – and the feature most needing explanation – is not their lack of distress but their happiness at having participated. Drawing on material in Box 44 of Yale's Milgram archive we argue that this was a product of the experimenter's ability to convince participants that they were contributing to a progressive enterprise. Such evidence accords with an engaged followership model in which (1) willingness to perform unpleasant tasks is contingent upon identification with collective goals and (2) leaders cultivate identification with those goals by making them seem virtuous rather than vicious and thereby ameliorating the stress that achieving them entails. This analysis is inconsistent with Milgram's own agentic state model. Moreover, it suggests that the major ethical problem with his studies lies less in the stress that they generated for participants than in the ideologies that were promoted to ameliorate stress and justify harming others.

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., & Birney, M. (2014).

Nothing by mere authority: Evidence that in an experimental analogue of the Milgram paradigm participants are motivated not by orders but by appeals to science. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 473-488.

doi:10.1111/josi.12072

- Abstract: Milgram’s classic studies are widely understood to demonstrate people’s natural inclination to obey the orders of those in authority. However, of the prods that Milgram’s Experimenter employed to encourage participants to continue the one most resembling an order was least successful. This study examines the impact of prods more closely by manipulating them between-participants within an analogue paradigm in which participants are instructed to use negative adjectives to describe increasingly pleasant groups. Across all conditions, continuation and completion were positively predicted by the extent to which prods appealed to scientific goals but negatively predicted by the degree to which a prod constituted an order. These results provide no support for the traditional obedience account of Milgram’s findings but are consistent with an engaged followership model which argues that participants’ willingness to continue with an objectionable task is predicated upon active identification with the scientific project and those leading it.

Reicher, S. D., Haslam, S. A., &, Miller, A. G. (2014).

What makes a person a perpetrator? The intellectual, moral, and methodological arguments for revisiting Milgram’s research on the influence of authority. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 393-408.

doi:10.1111/josi.12067

- Abstract: In this article, we outline the rationale for reexamining Milgram’s explanation of how ordinary people can become perpetrators of atrocity. We argue, first, that any consideration of these issues cannot ignore the impact of Milgram’s ideas in psychology, in other disciplines such as history, and in society at large. Second, we outline recent research in both psychology and history which challenges Milgram’s perspective—specifically his “agentic state” account. Third, we identify the moral dangers as well as the analytic weaknesses of his work. Fourth, we point to recent methodological developments that make it ethically possible to revisit Milgram’s studies. Combining all four elements we argue that there is a compelling and timely case for reexamining Milgram’s legacy and developing our understanding of perpetrator behavior. We then outline how the various articles in this special issue contribute to such a project.

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., Millard, K., & Birney, M. (2014).

Just obeying orders? New Scientist, No. 2986 (September 13), 28-31.

-

Introduction: If you only know about one research programme in psychology, chances are it is Stanley Milgram’s “shock experiments”. Conducted in the early 1960s at Yale University, the participants were asked by an “Experimenter” to take on the role of “Teacher” and administer an escalating series of electric shocks to a “Learner” in the next room when he chose the wrong answers in a memory test. This was supposedly part of a study into the

effect of punishment on learning. The participants didn’t know that the shocks, and the cries they elicited from the Learner, weren’t genuine. Nevertheless, many acceded to the Experimenter’s requests and proved willing to deliver shocks labelled 450 volts to the powerless Learner (who was in fact a stooge employed by Milgram to play this role).The power of these studies was that they appeared to provide startling evidence of our capacity for blind obedience – evidence that inhumanity springs not necessarily from deep-seated hatred or pathology, but rather from a much more mundane inclination to obey the orders of those in authority, however unreasonable or brutal these may be. This was the substance of the “agentic state theory” that Milgram developed to explain his findings in his 1974 book Obedience to Authority. Importantly, it is an analysis that chimes with political theorist Hannah Arendt’s notion of the “banality of evil”, which she famously developed after observing the trial of the Nazi bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann. Milgram’s studies are influential to this day, but are also some of the most unethical ever conducted in psychology. They could never be carried out in a similar form today due to the extreme stress suffered by the participants. Ironically, these ethical problems have served only to consolidate the influence of Milgram’s agentic state explanation. The impossibility of replication has made it hard for an alternative account to gain traction. Nevertheless an alternative account is needed. Not only have recent historical studies led researchers to question Arendt’s claims that Eichmann and his ilk simply went along thoughtlessly with the orders of their superiors, but reanalysis of Milgram’s work has also led social psychologists to cast serious doubt on the claim we are somehow programmed to obey authority.

Reicher, S. D., Haslam, S. A., & Smith, J. R. (2012).

Working toward the experimenter: Reconceptualizing obedience within the Milgram paradigm as identification-based followership. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 315-324.

doi: 10.1177/1745691612448482

- Abstract: The behavior of participants within Milgram’s obedience paradigm is commonly understood to arise from the propensity to cede responsibility to those in authority and hence to obey them. This parallels a belief that brutality in general arises from passive conformity to roles. However, recent historical and social psychological research suggests that agents of tyranny actively identify with their leaders and are motivated to display creative followership in working toward goals that they believe those leaders wish to see fulfilled. Such analysis provides the basis for reinterpreting the behavior of Milgram’s participants. It is supported by a range of material, including evidence that the willingness of participants to administer 450-volt shocks within the Milgram paradigm changes dramatically, but predictably, as a function of experimental variations that condition participants’ identification with either the experimenter and the scientific community that he represents or the learner and the general community that he represents. This reinterpretation also encourages us to see Milgram’s studies not as demonstrations of conformity or obedience, but as explorations of the power of social identity-based leadership to induce active and committed followership.

Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2012).

Contesting the ‘nature’ of conformity: What Milgram and Zimbardo’s studies really show. PLoS Biology, 10(11), e1001426.

doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001426

- Abstract: Understanding of the psychology of tyranny is dominated by classic studies from the 1960s and 1970s: Milgram’s research on obedience to authority and Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment. Supporting popular notions of the banality of evil, this research has been taken to show that people conform passively and unthinkingly to both the instructions and the roles that authorities provide, however malevolent these may be. Recently, though, this consensus has been challenged by empirical work informed by social identity theorizing. This suggests that individuals’ willingness to follow authorities is conditional on identification with the authority in question and an associated belief that the authority is right.

Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2011).

After shock? Towards a social identity explanation of the Milgram ‘obedience’ studies. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 163-169.

doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02015.x

- Abstract: Russell's forensic archival investigations reveal the great lengths that Milgram went to in order to construct an experiment that would ‘shock the world’. However, in achieving this goal it is also apparent that the drama of the ‘basic’ obedience paradigm draws attention away both from variation in obedience and from the task of explaining that variation. Building on points that Russell and others have made concerning the competing ‘pulls’ that are at play in the Milgram paradigm, this paper outlines the potential for a social identity perspective on obedience to provide such an explanation.

Quotations

Overview

The quotations on the following pages have been selected to give an insight into some of the key points that have emerged from debate surrounding the BBC Prison Study. These may help stimulate class debate, or prove useful when writing essays or preparing for exams.

The first set of these quotations relate to Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment and the various controversies this has fueled. The quotations on the subsequent pages relate first to the rationale and findings of the BBC Prison Study, and then to its broader implications for psychology and society.

A selection of these quotations can also be downloaded as a two-page pdf document here. This can be printed out for use as a class handout or as a study aid.

Quotations

On the SPE

The following quotations relate to the theoretical ideas associated with Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment (the SPE). They also point to critiques of these ideas that have been provided by other researchers.

Guard aggression … was emitted simply as a ‘natural’ consequence of being in the uniform of a ‘guard’ and asserting the power inherent in that role.

1 Haney, Banks & Zimbardo, 1973, discussing findings of the SPE

Participants [in the SPE] had no prior training in how to play the randomly assigned roles. Each subject’s prior societal learning of the meaning of prisons and the behavioural scripts associated with the oppositional roles of prisoner and guard was the sole source of guidance.

2 Zimbardo, 2004

The idea that groups with power automatically become tyrannical ignores the active leadership that the experimenters provided [in the SPE]. Zimbardo told his guards: “You can create in the prisoners … a sense of fear to some degree, you can create a notion of arbitrariness that their life is totally controlled by us…. They’ll have no freedom of action, they can do nothing, say nothing that we don’t permit. …. We’re going to take away their individuality in various ways".

3 Haslam & Reicher, 2005

It is not, as Zimbardo suggests, the guards who wrote their own scripts on the blank canvas of the SPE, but Zimbardo who created the script of terror.

4 Banyard, 2007

The fact that Zimbardo’s analysis [is] invoked in order to deny responsibility for acts of appalling brutality should serve as a warning to social psychology. For it points to the way that our theories are used to justify and normalize oppression, rather than to problematize it and identify ways in which it can be overcome. In short, representing abuse as ‘natural’ makes us apologists for the inexcusable.

5 Haslam & Reicher, 2006

Behind the tyranny of the prison guards and the abasement of the prisoners in the SPE, there is a view of human beings as the psychological prisoners of society … working out of a dysfunctional and inescapable human nature.… Social psychology spends much of its time explaining how society is reproduced, how the present recapitulates the past and very little on the other half of the problem, how and why society changes.… Society is not a psychological prison but a means of expanding human possibilities. A reorientation of theoretical emphasis is overdue.

6 Turner, 2006

Sources

1 Haney, C., Banks, C. & Zimbardo, P. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Review 9, 1–17 [Reprinted in E. Aronson (Ed.), Readings about the social animal (3rd ed., pp. 52–67). San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman]. (p.12)

2 Zimbardo, P. (2004). A situationist perspective on the psychology of evil: Understanding how good people are transformed into perpetrators. In A.Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil (pp.21–50). New York: Guilford. (p.39)

3 Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2005). The psychology of tyranny. Scientific American Mind, 16 (3), 44–51. (p.47)

4 Banyard, P. (2007). Tyranny and the tyrant. The Psychologist, 20, 494-495. (p.494)

5 Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2006). Debating the psychology of tyranny: Fundamental issues of theory, perspective and science. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 55–63. (p.62)

6 Turner, J. C. (2006). Tyranny, freedom and social structure: Escaping our theoretical prisons. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 41–46. (pp.41,45)

Quotations

On the BPS: Findings and conclusions

The following quotations concern some of the key findings and conclusions of the BBC Prison Study (the BPS).

The BBC Prison Study was designed to examine the factors that determine how people respond when a system of inequality is imposed upon them by others. At the start, almost all the participants rejected this system. However, by the end, they were close to instituting a new and more tyrannical social system…. This raises a new and unexpected issue. What are the conditions under which people create a system of inequality for themselves?

7 Reicher & Haslam, 2006

People do not automatically act in terms of group memberships or roles ascribed by others.

8 Reicher & Haslam, 2006

[Shared] social identity was a source of strength and resilience for the prisoners just as its absence was a basis for weakness and disintegration among the guards. United, the prisoners overcame their stress; divided, the guards buckled.

9 Haslam & Reicher, 2006

Failing groups almost inevitably create a host of problems for their own members and for others. These problems have a deleterious impact on organization, on individuals’ clinical state and … on society. For it is when people cannot create a social system for themselves that they will more readily accept extreme solutions proposed by others.

10 Reicher & Haslam, 2006

Authoritarians are only able to exercise leadership and set about creating an authoritarian world when circumstances move them from a position of extremism to one where they represent the wider group.

11 Haslam & Reicher, 2007

Sources

7 Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1–40. (p.24)

8 Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1–40. (pp.4-5)

9 Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2006). Stressing the group: Social identity and the unfolding dynamics of stress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1037–1052. (p.1049)

10 Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1–40. (p.33)

11 Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2007). Beyond the banality of evil: Three dynamics of an interactionist social psychology of tyranny. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 615-622. (p.620)

Quotations

On the BPS: Relevance for psychology and society

The quotations below concern the relevance of the BBC Prison Study for key issues in psychology and society.

One of the significant achievements of the BBC Prison Study is to show that, if sufficient care is taken, it is possible to run powerful and impactful field studies into social processes that are also ethical.

12 Reicher & Haslam, 2006

The rather remarkable conclusion of this simulated prison experience is that the prisoners dominated the guards! The guards became increasingly paranoid, depressed and stressed … Several of the guards could not take it any more and quit. The prisoners soon established the upper hand, working as a team to undermine the guards .… What is the external validity of such events in any real prison anywhere in the known universe? In what kind of prisons are prisoners in charge? How could such an eventuality become manifest?”

13 Zimbardo, 2006, commenting on the BBC Prison Study

In most prisons, even those where correctional authorities make a reasonable effort to maintain control of their charges, an inmate hierarchy exists by which certain prisoners enjoy a great deal of power…. This power imbalance is of course much more marked in prisons where the authorities have ceded effective control to the inmate population, an all too common occurrence.

14 Human Rights Watch, 2001, from a report on US State Prisons

The inmates seemed to be running the prison not the authorities.

15 Nelson Mandela, 1994, reflecting on his time imprisoned on Robben Island

The optimal conditions for the triumph of the ultra-right were an old state and its ruling mechanisms which could no longer function; a mass of disenchanted, disoriented and disorganized citizens who no longer knew where their loyalties lay; strong socialist movements threatening or appearing to threaten social revolution, but not actually in a position to achieve it.... These were the conditions that turned movements of the radical right into powerful, organized and sometimes uniformed and paramilitary force.

16 Eric Hobsbawm writing on the rise of Fascism in 1930s Germany

Our purpose is not to replace an analysis that sees prisons as inevitable sites of tyranny with one that represents them as inevitable sites of resistance. Rather, our dual objective has been to show that resistance is every bit as ‘natural’ as tyranny, and to attempt to understand the social psychological processes that determine the relative impact of these countervailing forces.

17 Haslam & Reicher, 2009

Sources

12 Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1–40. (p.34)

13 Zimbardo, P. (2006). On rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 47–53. (p.49)

14 Human Rights Watch (2001). No escape: Male rape in US prisons. Retrieved March 12, 2007 from www.hrw.org/reports/2001/prison/report.html

15 Mandela, N. (1994). Long walk to freedom: The autobiography of Nelson Mandela. London: Abacus. (p.536)

16 Hobsbawm, E. (1995). Age of extremes: The short twentieth century 1914-1991. London: Abacus. (p.127)

17 Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2009). The social psychology of resistance: Prison studies and the case for a more expansive theoretical imagination. Unpublished manuscript: Universities of Exeter and St. Andrews. (p.47)

Summary timeline

Table of interventions and outcomes

The table below provides a summary of key events in the study as they unfolded over time. In particular, it focuses on our experimental interventions and their impact on Prisoners, Guards and the prison system as a whole.

These interventions were devised on the basis of social identity theory, and key concepts relevant to the analysis that this theory provides are highlighted in red. These concepts are explained in the glossary, and we also provide a summary of social identity theory in our examination of ideas in depth.

A pdf of this table is downloadable here.

Quantitative data

Information

Every day during the study psychometric data were obtained from questionnaires that all participants completed. We also obtained physiological data by collecting saliva samples.

Alongside our qualitative observations, these two forms of quantitative data provided insight into the range of social, organizational and clinical processes in which we were interested.

This section presents some of the key data arising from statistical analyses reported in various scientific publications arising from the study.

Quantitative data

Social identification

Scores on social identification scales supported observational data in revealing a significant statistical interaction between group and phase. Further analysis showed that social identification among the Prisoners increased significantly over time. On the other hand, social identification among the Guards declined as the study progressed, but not significantly.

- Source: Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1-40.

Quantitative data

Depression

Overall levels of depression were low, but they varied as a function of participant group and phase. Specifically, while the Prisoners were more depressed than the Guards at the start of the study, by its end, this situation had reversed.

This pattern was confirmed by analysis which revealed a significant statistical interaction between participant group and phase. Further analysis showed that the Prisoners’ depression decreased significantly over time. The Guards’ depression increased over the course of the study, but not significantly.

- Source: Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1-40.

Quantitative data

Stress

Analysis of stress measures revealed a significant statistical interaction between group and phase. Further analysis indicated that this arose from the fact that on Day 6 the Guards were significantly more stressed than the Prisoners, and significantly more stressed than they had been on Day 2.

Analysis of the cortisol in participants’ saliva revealed a statistically significant effect for phase. Cortisol levels were higher on Day 6 than on Day 2. There was also a marginally significant interaction between group and phase, suggesting that this increase was more marked for the Guards than for the Prisoners.

- Source: Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2006). Stressing the group: Social identity and the unfolding dynamics of stress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1037–1052.

Quantitative data

Leadership

Responses on a measure of perceived group leadership revealed a significant statistical interaction between group and phase. Further analysis indicated there was a significant difference in the perceived leadership of the Guards and the Prisoners on Day 2, but no such difference on Day 6 (indeed, the pattern here had slightly reversed).

- Haslam, S. A. & Reicher, S. D. (2007). Identity entrepreneurship and the consequences of identity failure: The dynamics of leadership in the BBC Prison Study. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70, 125-147.

Quantitative data

Authoritarianism

Analysis of participants’ authoritarianism indicated that this increased significantly (for both Guards and Prisoners) as the study progressed.

As a variant on this analysis, we examined authoritarianism as a function of the groups to which the participants assigned themselves at the end of the study (i.e., as ‘New Guards’ who proposed setting up a new regime or the remaining Communards).

This analysis revealed a significant statistical interaction between group and phase. This reflects the fact that the authoritarianism of the New Guards had not changed over time, but that of the Communards had increased significantly. So while at the start of the study those who subsequently became New Guards were significantly more authoritarian than the Communards, this was not the case at the study’s end.

- Source: Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1-40.

DVDs to purchase

Original DVDs (4 x 1 hour)

DVDs presenting the four one-hour programmes (Conflict, Order, Rebellion, Tyranny) of The Experiment, as originally broadcast on BBC2 in March 2002, are available from BBC Active and Pearson Education. It is from these programmes that the various clips on this site are taken.

The DVDs are accompanied by electronic versions of (a) the 140-page manual written by the researchers and (b) the 190-page transcript of the programmes.

A flyer allowing the DVDs to be purchased at reduced price is available here.

If you want to order these via e-mail, please contact the publishers here.

DVDs to purchase

Teaching DVD (30 minute)

In response to increasing demand, it is now possible to obtain a DVD telling the scientific story of the BBC Prison Study. This has been produced through collaboration between the researchers and Online Classroom, a specialist producer of video-based educational resources.

In the main 30-minute presentation the researchers address key issues related to, and arising from, the study. This analysis is interwoven with extensive original footage from the study itself and is organized into five sections: (1) Setting Up, (2) Early Days, (3) Conflict and Order, (4) Rise and Fall of the Commune, and (5) Conclusions.

The DVD also contains a range of useful additional features, making it a perfect resource for teachers and lecturers. These include discussion of the ethical issues raised by the study, Q&A sessions with the researchers, presentation of quantitative findings, and an analysis of differences from the Stanford Prison Experiment. Key terms and concepts are also clearly flagged.

The DVD costs £39 +VAT (or around US$60). A preview clip can be accessed on the right-hand side of this page. Purchasing details are available from Boulton-Hawker films. [Note: The DVD contains no offensive language and is suitable for all classroom demonstrations.]

In February 2009 the DVD was reviewed by Psychology teacher Mark Holah on the influential Psychblog website. He wrote:

"The authors of the study have collaborated with onlineclassroom.tv and produced an excellent DVD which takes the viewer (student) through the important stages of their experiment. This is easily the best DVD that Online Classroom have produced so far in terms of editing, animation and use of original footage. More importantly [... the researchers ...] take the viewer (student) through an easy to understand and enthusiastic step-by-step description of their study.... I will be using the DVD as a revision lesson for my students this year and because of this will do a much better job of teaching this fab study next year".

The full Psychblog review can be accessed here.

Links

List of useful links

The following links should prove useful if you want to find out more about the background to the study and to the issues it addresses.

British Psychology Society Research Digest This site provides excellent resources for teachers and students of psychology, as well as an active and up-to-date bulletin board and discussion forum. The British Psychological Society also produces a range of other free resources for students and teachers, including samples of The Psychologist.

Social Psychology Network This comprehensive site provides access to a wide range of resources and contacts relevant to issues in contemporary social psychology.

BBC News Articles on the social psychological dimensions of abuse at Abu Ghraib.

The Stanford Prison Experiment This very popular and accessible site provides details of Zimbardo’s classic study.

Open University The BBC Prison Study has recently been included as part of the OU's social psychology course. This link contains a number of useful resources including a 12-minute downloadable podcast in which issues raised by the study are discussed.

OCR Exam Board From 2008 the BBC Prison Study has been included as one of the 15 "core studies" on OCR's very popular A-level Psychology syllabus. Indeed, this fact provided a major impetus for the creation of this website — enabling teachers and students to have easier acces to information and materials relevant to the study. This link is to a brochure that provides details of this course.

Glossary of terms

Information

This glossary provides definitions of terms and concepts that are commonly used in psychological literature and which are relevant to aspects of the BBC Prison Study. These are the same definitions that pop up when you move your cursor over words with a dotted underline throughout the website.

These definitions can be used as a focal point for teaching and discussion.